In an earlier post I have written about the importance of perspectives in a complex environment. Here, I am going to show how a well-known model can be used to systematically differentiate perspectives on an organisation, in order to be more conscious about how these perspectives shape the way we manage the organisation.

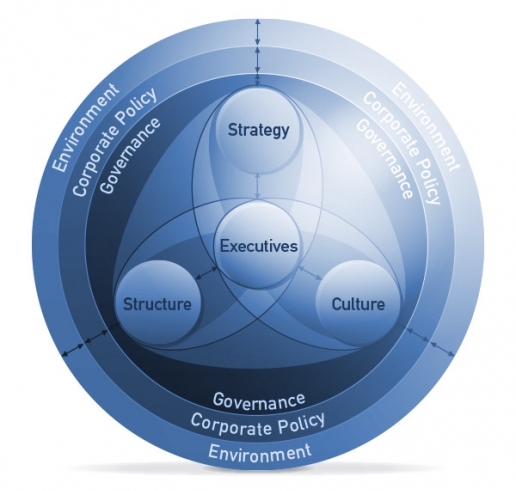

The model in question is so widely used in various versions that it proves difficult to name its inventor. In Fredmund Malik’s version, it includes strategy, structure and culture in a triangle, with executives at the center.

Other versions of this model leave out the executives, put people instead of culture, or use culture as a background to the whole triangle. Usually this model is used to point out how the various aspects of a company are interdependent, and that they need to be coherent with each other. You cannot expect a strong, cooperative team culture if your structure is built on separation, and your strategy on competitive incentivation of individual performance. You cannot expect a strategy to work when the necessary competencies (culture) are not in place. Etc.

However, this model is also very useful when you take its various elements to represent perspectives, and compare the focus the organisation puts on them relative to another. A company led over strategy will obviously have an elaborate strategy, which is then translated through a balanced scorecard or similar system of key performance indicators to the various contributing units, until it reaches the objectives for the individual person. There may be an incentive on reaching these objectives, but the question of “how” (a structural focus) is largely let for the contributor to decide, delegated down through the hierarchical levels. The company may also be relatively tolerant to “brilliant jerks” (which would be relevant under a cultural focus). As long as you deliver, your character is of little importance. The basic idea behind it is that if only people focus on delivering the right result, everything else is of little matter. Effectiveness comes over efficiency. Many sales organisations are led with this kind of focus. The advantage of putting this perspective in focus often lies in the drive and freedom delegated down to the executing levels, and in the capability to adapt to local contexts. In growing markets this may be of advantage, while in a saturated market, such organisations may struggle to maximize cost control, because this would require a level of coordination across units which contradicts the liberty of defining the “how” locally. People may reinvent the wheel at various points of the company at the same time.

By comparison, a company led with a focus on structure put much emphasis on the “how”. The accountabilities of various parts of the organisation are defined and confined against each other with a high degree of detail and accuracy. There are very precise job descriptions and RASCI charts describing who is responsible, accountable, who supports, who is consulted and informed over a certain issue. There are processes, procedures, workflows, standard operating procedures etc. The idea behind this approach is that the system is designed in such a way that if only people stick to their part in the process, the result will be fine. Efficiency and compliance come over effectiveness. Many organisations with a high element of safety are governed in such a way, such as power plants. Also, certified suppliers and highly regulated markets, such as the health sector, are managed in this way. The purpose of regulation through structure is to create reliability independent of the people involved. Often the advantage of this focus pays out when the nature of the business is very complicated, involving many parts which have to be coordinated with each other, and making it very difficult, and therefore expensive, for many people to understand how every little part interacts with everything else. The disadvantage is the risk to develop a bureaucracy with its own life, to become cumbersome and slow. It may be one of the reasons why heavily regulated industries such as the health sector or the construction industry, have a tendency towards heavily increasing cost.

Then there are companies with a strong focus on culture. If only people share the same basic beliefs and values, they can cooperate with a high degree of autonomy and be sure to do the right thing. In larger companies of this type you find elaborate decks on corporate values, hiring puts character over skills, and the informal conformity pressure is high. Companies with a strong founder story, or organisations with a higher purpose such as NGOs, are often managed in this way. I once visited a company famous for its bags made of recycled lorry tarpaulin and seatbelts. The manager explained to me that sometimes they had long, heated discussions about fundamental questions, that would surprise, or even put off outsiders. But once they had resolved the issue, there were no further discussions during the execution, and even low-skilled people worked with a high degree of autonomy and alignment. There lies the advantage: in situations where people’s aligned mindset is essential to allow for autonomous execution. On the other hand, anything that is difficult to explain or to be made meaningful, may prove a more difficult condition for such an organisation to strive. And since we know how difficult it is to change culture, it may be likely that the only companies successfully led with a focus on culture are those which are born that way.

And finally there are the companies with a focus on the key leaders. All the weight of the company’s success lies on the shoulder of the few heroes. Since they are so good and know what to do, as long as they decide everything, success is guaranteed. It is often start-ups which are managed in this way, especially if the founder, or the founders, are genius. The advantage is that such companies can be very fast, and disciplined – as long as they are small. Once the company gets bigger, these organisations often turn dysfunctional. I once had dealings with a company that was 23 years old, had over 2000 employees, and was still managed by the three original leaders. They worked seven days a week, usually until 11 p.m., and took every decision of a slightly elevated importance. The rest of the staff were used to being little soldiers in a constant state of operational frenzy. In other examples, the key heroes of the company are regional leaders, for example country managers, behaving like warlords and protecting the independence of the way their part of the organisation is operated. In a franchise organisation, this may be an advantage. As soon as coordination and alignment is needed, it’s a weakness.

As you can see, the emphasis put on the various perspectives on the company are not better or worse in comparison to each other. They all have their strengths and weaknesses. The first question is whether these potential strengths and weaknesses are yielded within the given approach. In addition, any given approach may be more or less apt to the context at hand. It is the context which defines whether a potential strength is of importance, or whether a given weakness can kill all efforts. And what is even more challenging is that contexts change, and what was once an apt approach, may now prove insufficient. Many of the most crucial, but also the most difficult change efforts within organisations are in fact a shift of focus between these four perspectives.

What is the dominant perspective in your organisation, and how does it play out?