In our previous posts, the nudging we have described addresses individuals. The relation to complexity is in the issues, the context these individuals find themselves in. It is the solutions that are supposed to emerge in the interaction of the individual and their problem. Even the public administration examples at the beginning of the chapter, while addressing large numbers of people, address them as individuals in the same type of situation, who are statistically influenced by the same type of nudge. It is an 1:n, or star-shaped relationship. But what if instead we nudge a complex system where the relationships are n:n, in form of a mesh network? Instead of sending the same letter to all the many individuals in a system, we do one or a few things to some individuals, and then they start doing things to others, and emergent behaviour happens not at individual, but at system level? For that, let’s have a look at the relations of mutual influence and interdependence in a complex system.

In the most successful cases, the uptake in the system, the n:n nudges, can be so strong they create an avalanche effect. In nature, such effects are called trophic cascades. A trophic cascade occurs when a change in the food chain, often at the top, creates ripple effects throughout the whole ecosystem. A famous example occurred in the Yellowstone National Park when wolves were reintroduced in 1995. Before that they had been extinct for many decades. During that time, the elk population, in absence of their most important predator, had exploded and damaged many parts of the environment. As could be expected, the 31 wolves had an immediate impact on that population, and in this unbalanced equilibrium, the wolf population started to grow, until it formed a homeostat, a balance of flow, between predator and prey. But more importantly, the wolves changed not just the number, but the behaviour of the elks. They started to avoid certain areas near the riverbanks where they could be easily trapped. And immediately the vegetation started to regenerate in these patches: higher grass, more bushes, more trees. This attracted smaller animals such as songbirds, mice, and rabbits, which in turn was good for the bears, hawks, and eagles. But much more surprising than that, the wolves changed the behaviour of the rivers. Due to the change in vegetation, the banks were more stable, and the rivers started to meander more. The current calmed down, which attracted more fish, otters, and beavers, which in turn contributed to stabilising the banks with their dams. A small number of wolves, distributed over a huge area, changed the appearance of the park’s geography. Obviously, the entire cascade had not been planned in detail by the people in charge. And, unlike the introduction of rabbits and frogs in Australia, it was known that a century earlier, there had been a stable ecosystem with wolves in that area. In recent years, it has also been found that this trophic cascade cannot be unilaterally attributed to the wolves, and that other conditions, including the change in temperature levels, played a role, too. Still, the relation between the little nudge and the overall effect remains impressive. And it continues beyond the park’s flora and fauna. According to the park’s visitor information centre, the park administration were surprised by the emotional effects the wolves had on the population. The struggle between some locals and demonstrators that were attracted to the case, led to lawsuits, which in turn created a nationwide response of public opinion and impacted federal environmental legislation.

In the social sphere, a good example of similar cascades can be seen in viral and content marketing. A master of this craft are Red Bull, who organise sporting events and celebrate unusual feats such as soapbox races and Flugtag around the world, which in turn attracts media attention and augments brand identity and visibility. For example, Felix Baumgartner’s record-breaking high altitude jump cost about 50 Million Euro to produce, but created worldwide media attention for Red Bull of a value estimated between one and eight Billion Euro. Once the record is news, the cascade is bound to gain momentum. It is almost impossible for a media outlet not to give air time to the event, and the name Red Bull cannot be avoided in the context. The point isn’t to directly reach many people. The point is to reach multipliers, influencers, and play to their interest. And they will reach many people. In the case of Baumgartner, the multipliers were media outlets. Many brands use celebrities as brand ambassadors with the same effect. It is not their appearance on advertising that makes the difference, but the appearance of the brand on the celebrities’ social media posts and on events covered by the media. Even bad actors, such as political disinformation troll farms, use the same principle. They don’t just address people willing to believe and share their posts on social media. It suffices to make their disinformation interesting to commercially oriented clickfarms. The clickfarms are not tied to the political interests of the trolls. It suffices that they are disinterested to the content or its morality, other than its capacity to go viral – a feat easier achieved by invented stories such as Pizzagate, in comparison to those bound by truthfulness. Acting as an amplifier, the clickfarms prefer to multiply the disinformation content because it helps them get more clicks, that lead to advertising money. And of course, in this instance, the nature of social media algorithms, which amplify and prioritise posts that create emotional engagement, play to these interests.

Such amplifiers – enabling constraints, as we shall see – can on the other hand also be the leverage point of nudges that intend to divert from a potential attractor. If our intention is to prevent a potential outcome, we should find what translates a tolerable system behaviour into something bigger, stronger, more sustained – and then remove the translator. During the early years of the second Iraq war, a small city would see violent riots break out in its streets and squares on a regular basis. These riots were not planned, but emerged from relatively small groups of people discussing or protesting something. More people would stop, listen, participate in the debate. The crowd would get so big that food vendors set up their stalls nearby. Over several hours, the crowd would get angrier, and at one point a small act of physical violence would turn the whole gathering into a violent riot. What was the solution? The government banned mobile food vendors. As a consequence, the crowds would dissolve and go home to eat before it came to violence. To the mobile food vendors, this was more than a nudge: they were basically driven out of business by this war-time executive decision. But to the crowd, it was a nudge: it was still possible to get something to eat – only it was more difficult because the number of places that sold food could no longer swiftly adapt to the ad-hoc concentration of people. There was a misfit in the choice architecture.

While examples of trophic cascades involve large complex systems with a huge number of agents, the same effect can be observed and employed on a smaller scale. When our daughter was little, I was soon perplexed about the arrangement for pushchairs and prams in public transport. Most trams and buses provide a dedicated area. You push your pram in a straight line from the low-threshold door to the other side of the vehicle and lock it in place. While this is very convenient for getting in and out, it is less so for the little kids. Almost all pushchairs are forward facing, so the toddlers sit facing the wall below the window. It comes as no surprise that many get bored quickly and soon voice their discontent. Some parents ignore it, others try a continuous sequence of distracting tools (picture book, dummy, teddy, bottle, smartphone…), and others awkwardly step to the other side of their buggy to be face to face with their kid – as the sole source of entertainment.

I made an eye-opening discovery when for the first time I turned the pushchair 90° so that my daughter faced whoever sat on the next seat – facing her. Most of the people reacted in a positive way, and started to interact with the kid, especially since I quickly learned to turn away and not get involved. As a result, my daughter learned that the world was full of interesting people who were being nice to her, that it was rewarding if she interacted positively with them, and she certainly didn’t get bored. Over time, she even insisted on it. If occasionally a businessman in suit and tie would try to avoid breaking character by talking gibberish to this little girl, she would pull on his sleeve and make him change his mind. Patterns emerged and became stronger because of an increase in self-reinforcing positive feedback loops. Similar things happened on the playground. I would take my little daughter to an interesting context – a group of children doing something she could relate to – and step out of the way.

I observed the most masterful application of this principle to the workplace when we were asked to offer a training program to a large European company. The company was the result of several acquisitions and mergers, all of which preserved their brand on the market, and to a large extent also their internal organisation and culture. The favourite metaphor used by the CEO to explain both strategy and organisation was that instead of becoming a huge tanker, the company wanted to act as a flotilla of speedboats. However, the head of people development observed that these speedboats – most notably the separate country organisations of each brand – were not managed as professionally as one could hope for. Many country managers had not even once attended a systematic management training in their career. Their methods and styles were wildly different, incompatible, and of varying quality. But, given the speedboat doctrine, they had an amount of power and independence akin to warlords in a feudal society, and the appropriate level of self-esteem to go with. When the HR department reached out to offer them a systematic, unified senior management training, it was therefore no surprise that their reaction was rather deprecating: “Sure, we could do such a training, as long as it doesn’t take much time. I could show my colleagues how it’s done” was the answer of almost each of them. After some inspired re-thinking, the head of people development proposed something different: a management foundation training for all the team leaders. That, the warlords accepted, pointing out how the juniors were still early in their development, obviously not on a same level as themselves, and how such a training would certainly be good for them. And so the program started. But now, slowly, slowly, all the junior managers in the company started to display a visibly more professional and systematic approach to management, in synch across all the units. Some would say, the juniors started to do their job better than the seniors. And all of a sudden, the head of people development was receiving those phone calls that he had hoped, and intended, to receive all along: “Listen, do you perchance have a really good senior management training that I could go to, preferably outside the company, and better than what the others could get?”

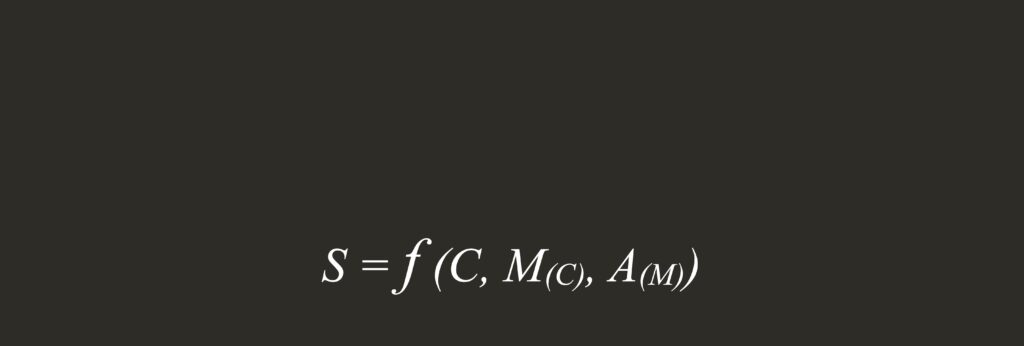

Nudging a complex system, it appears, implies an educated improvisation with the given dispositions and occasions. We strengthen the elements that can be strengthened with a reasonable amount of energy. We use conditions and contexts as a relevance filter that show or attract leverage points, or actors that we can use for leverage points, for our next intervention. We adapt the choice architecture of actors that we want to influence. We look for possibilities to make desired outcomes, both for ourselves and for these actors, easier to achieve and more effective in their impact. Inversely, we accept that all sorts of undesirable outcomes happen, but find ways to make them less likely, and especially less impactful, to the point that we and our actors in focus can afford not to care about them. We let the system play to our favour.